How Worthwhile Is It to Sign Critical Players Early?

Analyzing the increasingly popular trend of signing key players to long extensions early.

Introduction

Extensions while players are still under team control have risen in popularity in recent years, and have steadily trended towards being earlier and earlier in players’ careers. By my count, the Braves have 7 on their books alone, and teams like the Diamondbacks, Brewers, Red Sox, and Royals have also weaponized them to retain talented young players at well below-market prices long-term. They sound like a good idea in principle, but how much risk is there in forgoing several years of team control to lock in players at a nice discount versus letting them hit the market? How much value do arbitration extensions even provide when they go well? Should teams utilize them more? I think I’ve been able to get satisfactory answers to these questions with a good amount of data-collecting help.

Data Source

First things first. All the data I’ll be using was collected by the Youtuber Baseball’s Not Dead, who took the painstaking task of finding all the contract data, adjusting it for inflation, and considering what years of control were a part of the arbitration extensions. There were a few gaps that I filled in with the help of Spotrac and BaseballReference for the sake of comprehensiveness, but don't let that fool you. There are 650 different contracts in total, representing a database of all completed deals since modern free agency replaced the reserve system in the ‘70s. If you like my analysis here, I would implore you to watch some of the videos he made using the dataset, along with any of the other videos he’s put out, as his work is what made this deep dive even remotely possible. Here’s my favorite to start. At the end will be my spreadsheet where I “show my work”, because I’m obviously not going to be able to cover every nuance here.

Arbitration Extensions - Years of Control

First and foremost, we’re interested in extensions during and before arbitration. I’ve separated them by the amount and type of years of control left when the contract was signed, and have done some rudimentary statistical analysis on the general trends. What’s critical here is the sample size; once we go beyond extensions with more than 2 years of control, data starts to thin quickly. Therefore, I grouped (or “binned”) them by overall years of control, which will give a better signal of what’s going on. The primary metric of interest is additional value created by the extension, which is calculated by comparing a contract’s overall valuation to the value of the WAR they generated during their free agent years, and the surplus value they generated during their arbitration years (the difference between the salary they were likely to get throughout arbitration versus what the extension actually paid them). This is calculated on a per year basis.1 WAR is worth around $9 million, and it’s all inflation-adjusted of course.

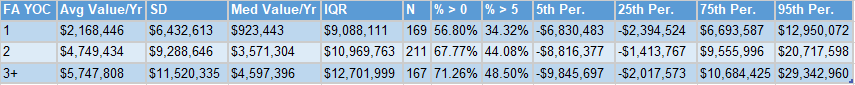

A breakdown of arbitration extensions by various center and spread measures.

I should first quickly go over what’s in the table here, from left to right, because a similar format will be used in several tables presented later. The first column holds the bins for the years of control (YOC), with the 4+ bin including any deal that covers a year of minimum salary (or all 4 arbitration years of a Super 2 player, in rare cases). Next are the average and median marks per year, representing the center of each bin, and the standard deviation (SD) and interquartile range (IQR), indicating the spread, or variance, of the data. Often when I reference the concept of “variance,” I’ll be invoking both measures, even though it may be semantically questionable to describe IQR that way.

The values in these datasets are quite heavily skewed, with poor-performing, negative WAR-generating players likely to be benched and barred from accruing further negative value, making it far easier for players to reach outlier positive marks than negative ones. This means the average will be slightly inflated, and the median will give a better idea of the actual midpoint of what one can expect. As a result, I favor using IQR over SD to indicate the amount of dispersion in the values, with IQR representing the difference between the observed 75th percentile and 25th percentile outcomes.

The distribution is clearly skewed towards positive extensions, with a limit to the amount of bad play a team can stomach. Each bin is from the shown value to the next interval factor of 5 (i.e., the highest is 45-50).

N is the sample size, and it’s clear that the 4+ year bin is the smallest. Obviously, teams try to avoid losing years of players at the minimum salary, despite it providing the greatest opportunity for a discount, but in recent years, this has grown in popularity for reasons that I’ll go more into detail on later. ‘% > 0’ is the number of extensions that return a positive added value per year, which I deem ‘a positive return’, and ‘% > 5’, the rate of deals creating more than $5 million of value per year, known as “great value” deals henceforth. The latter is the type of profit you’d be hoping for when you take on this type of risk. Lastly are the percentiles, which are fairly self-explanatory.

Back to business. There’s a clear relationship between when the contract is signed, and its corresponding risk/reward. The lowest variance is offered by the deals done with 4 or more years of control remaining, by a significant margin, mind you, but there is a similarly low reward in both median and average values. A higher variance isn’t always a bad thing - a higher-risk asset often has a better chance of a spectacular outcome - but I would generally subscribe to lower-risk investments in this instance. You’re already getting a player’s prime years - a safe single is better than taking a shot at the low chance of a home run.

Using that lens, the low dispersion of deals made 4+ years before free agency makes the odds of the contract finishing above-water about the same as the later deals, but the odds of a great piece of business diminish by 12-16% - a safe, but efficient investment. In fact, the only player to finish below -$5 million/year (~.5 WAR less per season than expected by their salary) is Preston Wilson; despite only 11% of deals being signed this early, they make up just 1.2% of those that perform that poorly. In total, there were 35 deals that did straight-up worse than Wilson’s. Deals signed with 2-3 YOC appear to be the best, taking advantage of several years of arbitration to get some extra margin while not needing to concede minimum salary seasons. It has the highest median profit, and the best ‘positive return and ‘great return’ rates, while sacrificing only a little bit of extra risk. I wouldn’t be confident that 2-3 YOC extensions are the best from an efficiency standpoint without more thorough research, but the sample size is relatively significant, and seems like the proper balance of risk-reward in the most general case.

Arbitration Extensions - Pitcher/Hitter and FA YOC

The pitcher/hitter dynamic is also important to focus on. How volatile are pitcher extensions relative to hitter ones? It’s a common refrain to say that pitchers are riskier investments than hitters, and that’s certainly borne out here. Hitter extensions are $3 million more fruitful in median value, a 12.5% higher net-positive rate, and a 10% higher great return rate. Such a large disparity explains why hitter extensions are nearly twice as numerous as pitcher ones. Over time, this gap has decreased, from a ~20% gap in the ‘80s to just 4-5% now (including more “great moves” for pitchers than hitters in the 2010s!), but that’s more due to a dramatic falloff of hitter value than anything the pitchers did. I’ll get back to this point, don't worry.

Hitters are clearly a safer investment than pitchers, like most would intuitively believe.

Lastly, one can look at the number of free agent years that are covered by the extension (I call them FA years of control to avoid confusion later). While it is likely that one will keep a player for the entire duration of their team control years, that is not necessarily true for their free agent years. The more free agent YOC, the larger the risk. As the contracts increase in FA YOC covered, the average and median return increases, which allows it to contain more of a player’s prime, but also allows more time for something to go wrong. In this case, that’s a good thing: the upper bound goes up far more than the lower bound goes down, which is why teams often want to tack on as many free-agent years as possible when doing these deals (along with the typical bonus of them being team or mutual options). If one can get 3 or more FA years included, the odds of getting a positive return is a staggering 71%. There is an important caveat - top players will exclusively get such a large amount of FA years included, so it's skewed towards the better talent. Unfortunately, the small sample of the bin makes a deeper dive very difficult. While the bin is 3+ FA years of control, almost two-thirds of the data comes from 3 years precisely.

Before I finish this section, it’s worth noting that an important variable omitted from this analysis, which would be especially useful in this section, is the age of the player when the extension began. While the general trends seen here can be explained by guaranteeing a higher salary during the years when a team usually gets its best value, in exchange for a lower salary during the years the player would be in free agency, it also can be explained by the aging curve.

There’s little time for a player to age out if they sign a 10-year extension at 23 at 4+ years of control, but there’s far more risk from a value perspective than a 7-year extension before their last year of arbitration at 26 or 27 - their best years may be mostly behind them. Teams avoid making such deals outside of elite talent, hence the great returns on those 3+ FA year extensions.

While a lot of this section seems intuitive, I think this point is the most interesting, considering the relatively small sample of deals made before arbitration. If teams offered more pre-arbitration extensions to very young players, could they maintain the low variance while cashing in solid returns, before allowing them to hit the market at an older age than usual (either depressing their value for a further deal, or letting them go after the prime)? The Braves seem to believe this is possible, and are trying to push the advantage to the utmost extent.

Free Agent Deals

In this part of the analysis, I will look at deals solely $100 million or more, adjusted for inflation, again thanks to Baseball’s Not Dead database. This makes some sense since any player you’d consider signing to an arbitration extension probably would be expected to get $100 million on the open market, inflation-adjusted. One could also adjust for the cap, considering it actually grows a little faster than inflation (~3% per year), but I’m not sure that’s worth almost anyone’s time - just expect the number of inflation-adjusted $100 million deals to grow over time naturally. This dataset contains 89 deals overall.

Free agency deals 7 years and above almost always end in serious buyer’s remorse.

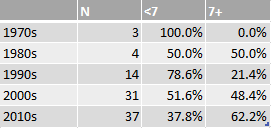

Big free-agent deals, as one may expect, do not return great margins. The average Arb or Pre-Arb deal performs better than every FA deal averaged by year, in terms of average added value, the percentage that are above 0, and the percentage that are great deals. 4-6 year deals find an equal proportion of great value deals and a slightly reduced amount of average value ones, but after that, it falls off a cliff. Deals of 7 years or more earn their keep only 42% of the time, and great value 20% of the time, while running negative average and median scores. The most dangerous thing, in my mind, is the corresponding decrease in SD and IQR; while you maintain the same floor, the higher upside deals aren’t nearly rewarding enough. 7-8 year deals typically just have the upside of an average Arb extension, with far greater risk attached, and 9+ year deals are somehow even worse. The analysis makes clear that deals above 6 years should be heavily scrutinized, as they often turn sour long before the signing team may have first suspected.

This graph may be slightly confusing: we’re no longer talking about the number of FA years tacked on to an arbitration extension (FA YOC), we are now talking about the length of deals signed in free agency (top two rows), versus years of control when Arb deals were signed (bottom three rows).

Pitchers and hitters are far more similar in FA deals than arbitration ones. They both see great value around a third of the time, but hitters are more reliable, seeing positive value about 10% more. While the median hitter contract is slightly above water at $600k per year added value, the median pitcher contract is a -$5 million per year disaster. The median is especially important here; deals like Randy Johnson’s with the Diamondbacks, which is the best one in the entire database, from Arb or FA, can drive up the mean to an incredible degree.

Recent Trends

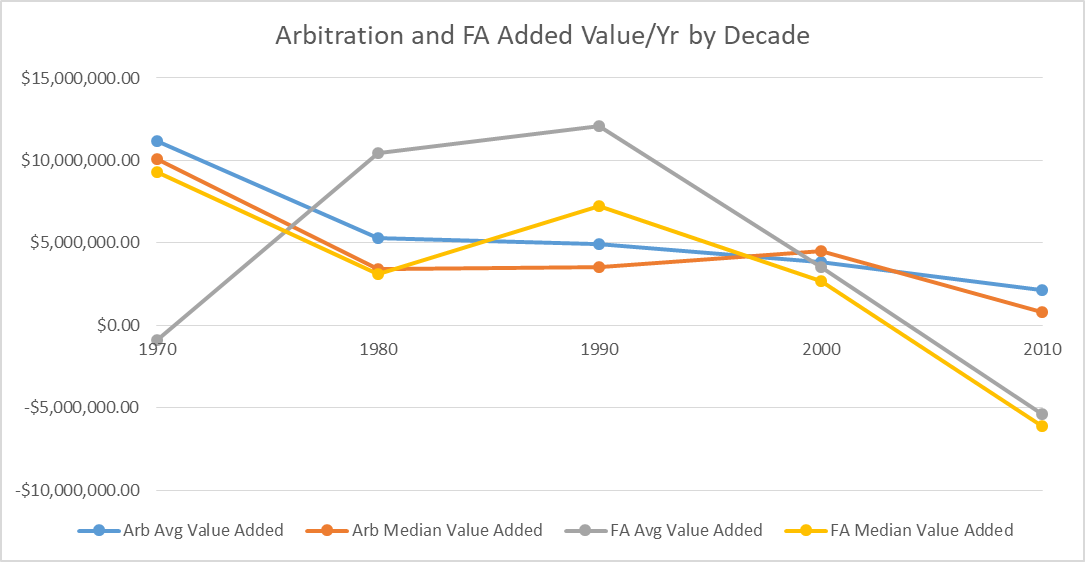

I alluded to it earlier, but I made this a separate section because I think it’s extremely interesting. When analyzing these deals by decade, both FA and Arb, there’s been a clear step-back in efficiency in these types of deals compared to every other decade. Arb extensions lost $2 million in average value, nearly $4 million in median value, and $1 million in SD and IQR in the 2010s compared to the 2000s, which results in far less upside for very similar downside, like the 4-6 vs 7+ year FA contract comparison. Correspondingly, these extensions have lost 8% from their evergreen 67% success rate, and 15% in great value rate, down to only 60% and 30% respectively. FA deals are even worse: the average and median are down around $9 million per year, and both the ‘>0’ and ‘>5’ rates were cut in half, to an appalling 33% and 20% respectively. In other words, 2 out of 3 $100 million deals were not worth it all, and 4 out of 5 probably weren’t worth the trouble.

The ‘80s and ‘90s were the golden generation of outlier free-agent deals (notice the median is far below the average, indicating lots of positive outliers), but now, free-agent deals are often best to forget.

It should be abundantly clear that arbitration extensions lost a lot of their luster, and big free agency deals are borderline unusable, except in the most obvious cases. Now, why is this the case? Have the analytics mob ruined player evaluation, and made teams pull the trigger too soon? I don't think so. I think teams entertain much longer contracts than they used to, both to indulge rising player demands and from the desire to lower the AAV hit from the corresponding deals for luxury tax purposes. Trea Turner and Xander Bogaerts are solid players, but there’s a good chance neither will make the Hall of Fame. They both got 11-year contracts. Guess how many other players have ever gotten 11 years or more in a completed free-agent deal? Zero.

They’re in good company, though. Yamamoto, Harper, Betts (I think it counts?), Trout (even less sure about this one…), Soto (soon), and Correa (if not for a medical) all join him, with the earliest signing coming with Trout and Harper, which both took effect in 2019. For arbitration deals? 1 completed contract has ever gotten that length, Troy Tulowitzki, with a couple checking in at 10. Presently, Tatis, Stanton, Julio Rodriguez, and Witt all enjoy a length of 11 guaranteed years or greater in that category, with many more at 10. Put simply: contracts are longer, and so logically, the tail end of the deals create massive negative values This comes as a correction from the ‘80s and ‘90s, where free agent value was especially plentiful, but it’s gone too far in the other direction. The market should correct and offer shorter deals, but I don't think it has yet, and may not for some time.

For reference, the following players had big FA deals that were of great value, by my definition, in the 2010s: Matt Holliday, Cliff Lee, Adrian Beltre, Felix Hernandez, Justin Verlander, Joey Votto, and Max Scherzer. By my count, 6/8 are Hall of Famers, one is the ever-elite Cliff Lee, and one is Matt Holliday somehow. So if you want good value on the FA market, go for a sure-fire Hall of Famer, a Holliday, or don't bother.

Outside of a small sample in the ‘80s, the rate of contracts being 7+ years continues to skyrocket upward, with seemingly no end in sight. Remember, this doesn’t metric doesn’t count any contracts that are ongoing (Turner, Bogaerts, Rendon, Seager, Semien, Cole, Judge…).

Here’s some historical perspective. When Barry Bonds signed with the Giants for the first time, he was 28, had 2 MVPs, just had a 198 WRC+ season (Juan Soto currently has a 190, for comparison), and set the record for the most money in an FA deal ever. He signed for six years. After winning another MVP, putting up a 40-40 season, and never dipping below a 160 wRC+, he signed for just three more. Greg Maddux, coming off a Cy Young and with a career 3.35 ERA at age 26, signed for five years. Yesterday’s price ain’t today’s price, and front offices have needed to adjust accordingly over the past 5-10 years.

FA deals in the 2010’s have provided, frankly, appalling value.

The cause for the arbitration regression is harder for me to pinpoint. Two things stuck out. First, the ratio of hitter and pitcher extensions is far less dramatic than prior decades, which would explain the drop in return on investment if hitters didn’t see a far larger drop in value than pitchers in that span. Secondly, there was a surprising lack of “home run” deals. Deals in the decade make up a clean quarter of all deals ever done, but the best only comes in at 24th all-time, they make up only 4 of the top 50, and 15 of the top 100. I’ll chalk it up to partially bad luck with the hitters and partially bad process with the over-indexing on pitcher extensions, because the bottom percentile deals are actually quite in line with every other decade. The lack of upside the deals provided is what’s costing them. First place? R.A. Dickey’s two-year deal which included his 2012 Cy Young season. Who would’ve thought.

In spite of seriously underperforming in the 2010’s, the free agent market’s nosedive in profit margin creates room for arbitration extensions to flourish. Before, they were slightly better in expected value, but now, they crush free-agent deals. Why wait until free agency for a star when you’re likely to get rinsed for a 9+ year contract? Might as well give them 9 years now instead and have the knowledge you could end up getting a good deal out of it. If the player is a long-term piece, it’s not necessarily a choice between paying them now or not paying them now - it’s often a choice between paying them now or paying more for less later. The rush to sign top prospects early is a clear indicator of that change in thought process.

Last point. Some argue these longer free-agent deals are OK because when stretching out the contract length, it lowers the hit to the cap, and correspondingly, the tax you need to pay. This would artificially lower the value per year, and treating the contracts like an annuity (adjusting for inflation and the tax threshold for each individual year, rather than just when it was signed), would be even more forgiving for the most recent contracts. Some go so far as to say the owners take the extra money they save from the extended contract, invest it in some high-return vehicle, and make a little extra cash that way. Let’s put it this way: I doubt the Padres owner will end up being happy that the Bogaerts extension was 11 years long, almost guaranteeing that he will be a complete non-factor for the last five years of the contract, instead of a more palatable 7 or 8-year deal (remember, those are still terrible value), simply for the opportunity to put a couple extra million in the stock market. Unless they bought NVIDIA with it, of course. Then they probably don't mind.

Conclusion

I think the evidence here is fairly clear. Arbitration extensions are an increasingly popular way to lock up talent at an early age while forgoing the ever-larger money pit that is the modern superstar free agent market at the same time. Certain teams being more willing to make financial sacrifices to go “all-in” than ever, enticing them to spend hundreds of millions on players that they hope will be somewhat playable in half a decade, appears to have resulted in a race to the bottom as prices continue to balloon and value metrics correspondingly plummet. While some teams have already dramatically changed course to take advantage of this serious arbitrage opportunity, I expect it to happen more and more in the coming years (next up, the Orioles?).

In the next day or two I’ll be posting a follow-up where I showcase a simple method I devised to project arbitration extensions, and then apply it to the top young players to see what it says. I came up with it while working on this article, and was surprised at how well it ended up doing when backtesting. This article is long enough already, so I chose to make it a separate, short addendum. See you then.

Sources

Baseball’s Not Dead (Many thanks again for the crazy amount of work collecting everything)

Spotrac

BaseballReference

My spreadsheet - The “Breakdown” tab is where the various metrics are calculated.