Luis Arraez's Chances of Beating the Odds

Baseball history has proved that hitting .400 is virtually an impossible task in the modern era. Can Arraez do it anyway?

Introduction

I won't be the first person to talk about Luis Arraez's historic season, but many people put it in perspective of those around him today. While that's a noble exercise, Arraez being one of the strongest candidates to hit .400 in the current era is not particularly impressive, given the game's evolution in the past twenty years. It's much more prudent to compare him to his historical peers; it is an absolute achievement rather than an era-relative one, after all. To start, one must ask, what does it take to hit .400, anyway?

Historical Comparison with .400 Hitters

I'll start by looking at every player who has achieved .400 since 1920, often considered the start of baseball's modern era. I picked 1920 because, before then, the game was extremely funky and would swing the data too much. For example, in one of my favorite historical tidbits, Ty Cobb led the league in home runs in 1909 with 9 HR, and all were inside the park. The parks had crazy dimensions, and the ball was dead - a combination that makes the results too foreign for even players of the 1950s to be appropriately compared to them.

According to this article by SABR and this one by Baseball Almanac, inside-the-park HRs were ~35% of all HRs at their peak and now make up ⅔ of 1% of HRs. Even in the 1930s, years considered modern by the typical definition, it was 5-8%. Using inside-the-park HR rates as a proxy for "ballpark weirdness," one could say that hitters of the 1920s benefitted from many of the same things the deadball hitters did. Hitting .400 is virtually impossible for any player, but given only two have done it since 1930, it's virtually impossible with modern conventions.

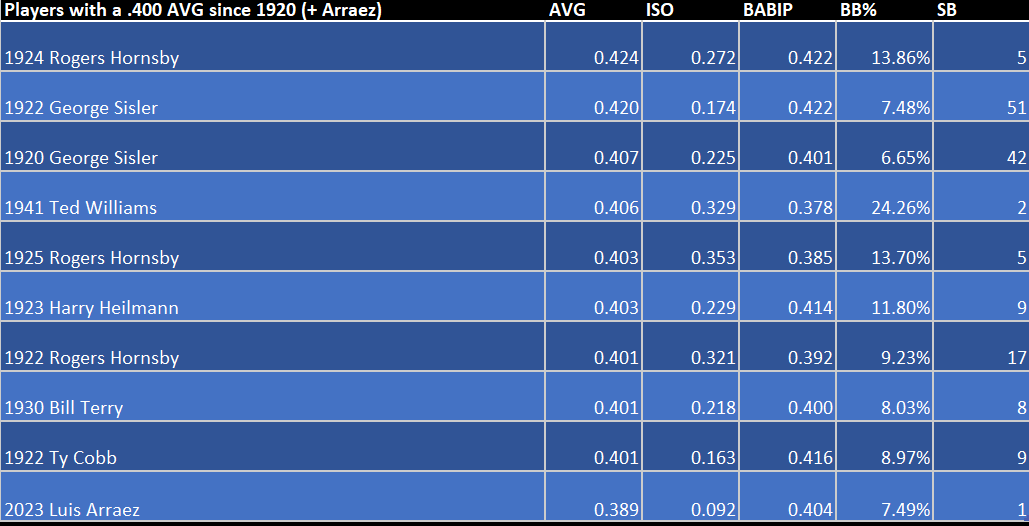

In any event, the list is concise, earning the milestone's lofty place in baseball lore. The columns in the chart represent the following:

ISO (Isolated Power) is calculated by subtracting AVG from SLG and represents raw power

BABIP (Batting Average on Balls in Play) represents bat control and general luck on balls in play. Anything above .360 is an outlier.

BB% (Walk rate) represents plate discipline

SB (Stolen Bases) represents speed. One could also use SB success rate, but I think SB is sufficient.

All play an important role - the one that may be controversial is the inclusion of power, but balls in the gap will lead to extra-base hits (XBH), which increases one's ISO while also being extremely likely to go for a hit. Besides Ty Cobb, who played over 100 years ago, every single .400 hitter had over 2x the power of Luis Arraez. To show that more clearly, here are the highest AVGs with an ISO of .092 or lower, Arraez's current level, since 1920 (what I've deemed the "modern age").

The thing to note here is that no player with the same level of power as Arraez has anywhere near Arraez's speed either (represented by SB) until Paul Waner, who has an AVG around .040 lower. In fact, you have to drop 25 points to get anyone at that level of power at all, Ichiro in his record-setting season of 2004. This makes one thing clear: Arraez has a weaker power/speed combination than any player who's ever contended for .400 in the modern age.

Modern Comparisons to Arraez

Here are the players often compared to Arraez in modern times, plus my own submission: George Brett in 1980. Ichiro and Gwynn are often seen as the spiritual predecessors of Arraez, but both had skills in these years that Arraez desperately lacks. Ichiro had generational speed that stole him many hits during his prime so that he could run a .357 BABIP during his peak in the 2000s as a Mariner. Tony Gwynn was similar to Arraez in skillset, but his only proper run at .400 came in the 1994 season, when he had an ISO almost double Arraez's current ISO, and far above his career average. Gwynn also managed an extremely high walk rate for his standards, at around 10%.

While many think the lockout cost him .400, I'm not convinced that he would have gotten it; he got to skip 50 games while doing exceptionally well in facets of the game he wasn't known for - power and discipline. His last full month, July, saw the lowest AVG (.375) and ISO (.140) of his season to that point, he never hit .400 for any whole month, and he just so happened to end the year with an exceptional .475/.512/.672 in 10 games to start August. Unlike my candidate, George Brett, he was holistically trending the wrong way in every category.

Brett started slow in 1980, and missed a month in the middle of June with an ankle injury. It might have been the best thing to ever happen to him, considering he hit .421/.482/.696 with a 10:38 K:BB ratio after that, winning the MVP despite missing 45 games. He had the speed and power required, with solid plate discipline and a very reasonable .368 BABIP in tow. If a couple more things went his way, he could have been the player with the lowest BABIP on the .400 list; even surpassing Ted Williams, who managed it with just a .378 BABIP thanks to 37 home runs and a generationally high walk rate.

Luck’s Role in the Pursuit of .400

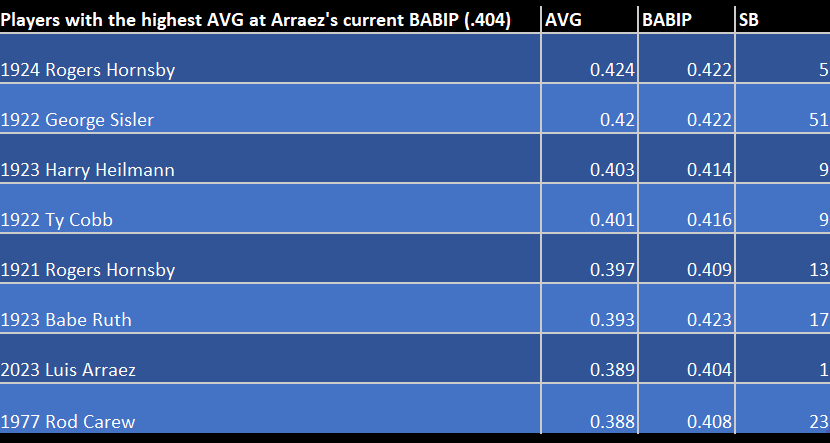

Now, I'll revisit the concept of BABIP. Only 10 qualified players have finished a season with a BABIP of .404, and I omitted the last 6 because they all had K rates that were far too high to compete for .400. As of the day of writing this, Arraez (obviously) and Brandon Marsh (?!) match this total as well.

While many believe speed is essential to a high BABIP, this list of results would disagree. Sisler and Carew were bona fide speedsters, but Hornsby and Ruth were perhaps average in that department, Ty Cobb was 36 and past his speedy prime, and Heilmann and Arraez weren't, and aren’t, known for their speed at all. BABIP has some solid correlation with speed, of course, but a solid line-drive approach, and straight-up luck, are far more critical. Why did Babe Ruth have a .423 BABIP in 1923 and .383 in 1924, when a year earlier, he was at just .320, and a year later, a .297? He wasn't doing extra sprints pregame - it was mostly just luck mixed with some added line drives in 1923 and 1924. That's what makes .400 so challenging - the lottery of BABIP is the deciding factor in many cases. If Brett had slightly better BABIP luck, he'd have gotten .400, and this article may not exist. Or anyone else close, for that matter.

Can Arraez Do It?

To put the findings here succinctly, one needs elite power or speed to reach .400 (I view BB rate as an extension of one's power - nobody wants to walk Arraez or Gwynn under normal circumstances). Arraez has neither, which means he likely will fall to the wayside like many other bat-control artists. People often say his ability to put the ball in play is why he's a contender, which is true. But that's a given - it's hard to get a hit 40% of the time when 25% of at-bats have no chance of a hit at all.

Power is the most crucial skill separating the genuine contenders and those who merely got close one year. League-median ISO has been .130 since 1920, yet every hitter who achieved .400 is well above that threshold. A steady diet of extra-base hits is crucial; slapping singles all the way there is too tall of a task. Only 1922 Ty Cobb and George Sisler are below-average in any year, and the few years that outpace them fall in the offense-heavy 2000s.

Some people cite the move to Marlins Park as a catalyst, but I don't see it. Marlins Park is dead-average in every type of hit except triples (which he only has 1 of) in park factor, so it's not like it's giving him a considerable advantage in terms of the outfield size. The Marlins do rank 4th in BABIP, but Arraez running a .403 is undoubtedly pulling the average of .315 up a bit. The individual qualified players are also pretty run-of-the-mill - Bryan de la Cruz has a .305, the rapid Jon Berti a .343, and then you get to Garrett Cooper all the way down at .316. Arraez may be slightly advantaged, but it shouldn't be decisive.

Arraez has achieved such a high BABIP for an extended period of time because of his ability to keep his batted balls in the optimal launch angle range for hits. Until now, he's posted a launch angle standard deviation of 20.5, which is extraordinary. Generally, 23 or better is elite, and 26-27 is average, so 20.5 is absurd. He's feasted on balls down in the zone to get there, but the cracks are beginning to show: he's struggled up in the zone with squaring up the ball, and as the Marlins catalyst offensively, he will be the one they gameplan against. His xBA is .332, which may be a little low, but I wouldn't say it's off by much; it even gives Seager (.338) and Acuna (.353) higher marks, presumably because of their superior XBH power. As mentioned prior, while his approach may give him strong BAs, it isn't enough to reach all-time great levels for an entire year.

He's down well in the middle and bottom part of the zone, but the upper third has given him significant trouble. Also, no zone in the strike zone has an xBA above .371. [BaseballSavant]

The Closest Contenders since 1941

I searched for all players since 1942 with an AVG > .375 and an ISO above .150, or the closest contenders with my loose criteria. Notice Gwynn is here in his unicorn season, and no Ichiro, Bonds, or Boggs. Truthfully, all these years are unicorn years where everything fell right into place - hence why there are only six entries despite only two reasonable parameters.

Ted Williams once said, "If I had known hitting .400 was going to be such a big deal, I would have done it again." I respect the self-belief, but other than in 1957, when he focused more on power than almost any other season of his career, he never got particularly close. In any event, I find him, along with George Brett, as the closest contenders. They had everything they needed to do it; they just needed some better fortune. Larry Walker and Stan Musial were too far away, and Rod Carew was buoyed by an absurd month of June where he hit .487 with a .300 ISO. Sadly, his power was insufficient otherwise. Consider it a case like Gwynn's from '94.

Who do I think is the closest now, other than Arraez, in a power-surge year? I'd say Ronald Acuña Jr. He's slashed his K rate by 11% this year to 12.6% while maintaining an excellent 11% walk rate and 5.5% HR rate. If he posted that K rate with his career-best 13.6% walk and home run rates from 2021, he would only need a .415 BABIP across to make it. With his speed, it's more likely that it’s him than virtually anyone else alive.

Conclusion

If Arraez does do it against all odds, will he win MVP? I would imagine so - voters love talking themselves into voting for the cool accolades when they happen, and if he does hit .400, it won't be with 3 or 4 HRs. He will need 6 or 7 more HR to make it a reasonable target, and at that point, he'd have a 165-170 wRC+ at worst. If people can talk themselves out of punishing him for his weak baserunning, defense, or mediocre power…he has a good chance. Remember when Miguel Cabrera won MVP over Trout simply because he got the Triple Crown? He took 22/28 first-place votes to win the award. This feat is even more unprecedented, and many people still believe that the choice in 2012 was the right call.

But remember, even if Arraez hits .405 for the first 120 games, he'll need .385 for the final 40 to make it. If he hits .410, he'll need .370 in the final 40. He can barely reach .400 right now, and one lousy stretch will send him tumbling down. A run-of-the-mill 3 for 20 stretch tumbles him down 20 points further. The only way I see it happening is if Arraez sits the rest of the year once he qualifies for the batting title and surpasses .400. Math doesn't care about extraordinary milestones, unfortunately.

This article was partly inspired by this video by Foolish Baseball about Votto’s .400 AVG in the 2016 2nd half.

Thank you to Stathead for the data that made the analysis and tables possible.

Sources

-BaseballReference/Stathead

-FanGraphs

-BaseballSavant

-SABR

-BaseballAlmanac